Drinking from a firehose. An overused metaphor, but it’s a pretty good way to describe the goals of this project. Project CyW-D (The Cyberwar Discourse Project) is funded by a grant from the College of Humanities at the University of Utah, and our mission is to track the shifting flows of discourse, debate, and rhetoric about cyber war.

This is a growing area of emphasis for politicians, military officials, businesses, infrastructure planners, and civil liberties advocates. Major American policies, including the Obama Administration’s proposal for Trusted Identities in Cyberspace and cybersecurity legislation pending in Congress, as well as international policies like ACTA and the State Department’s emphasis on “Internet Freedoms,” are all being influenced by contentious discussions of the threats – and hype – of cyber war. The distributed denial of service (DDOS) attacks against and on the behalf of Wikileaks have only heightened awareness of cyberspace as a battle ground. And of course, the continuing mystery and speculation surrounding the Stuxnet virus has made cyber war front page news. It seems every day has a news story trumpeting the coming cyber war as if this is a new, frightening, and inevitable outcome of our increasing use of the Internet.

However, this repeated and dominant cybersecurity discourse is not without its critics. Some observers contend that all of this talk of “cyber-warfare†simply involves threat inflation that has little to do with substantive domestic or international security issues. Various think tanks, corporate security firms, and business leaders who trumpet the problem of cyber attacks are portrayed as self-interested parties or ideologues who promote unrealistic portrayals of the power of hackers or other purveyors of “asymmetric warfare.†As Stephen Walt observed, even when very serious and “level-headed people†write about cyber attack incidents they often have a hard time actually documenting “how much valuable information was stolen or how much actual damage was done.” Tim Stevens has similarly worried that when “it comes to parsing and understanding the politics of cybersecurity,†there is a need for some oversight “over a system that is currently failing to curb the discursive excesses of powerful interests within government and industry.”

As academics, it is our goal to carefully interrogate this debate, mapping its flows over several matrices. First, we want to historicize the debate. How has it shifted over time? How have the alleged methods of cyber war changed? What is being threatened today, and is this different from past threats? And how have civil, business, and military policies changed in response to these alleged threats? This temporal matrix is extremely important: threats to and from cyber space have existed for as long as there have been computer networks (though most news reports tend to present cyber war and its cognates as something Brand New). Based on our initial research into government documents, op-eds, think-tank reports, and sundry blog posts, we believe that cyber war discourse has mutated significantly and even abruptly over the past several years, with potentially dire consequences for anyone who forgets this history.

Secondly, we want to map the network of actors involved in the debate. Who are they? What are they saying? What credentials do they claim? And very importantly, how might they stand to benefit from changes in cyber security policy? We believe that the political economy of cyber security – ie, the flows of immense wealth and power that are at stake due to the importance of communications networks – is a key area to consider, and we want to publish information about all actors involved.

Methodology

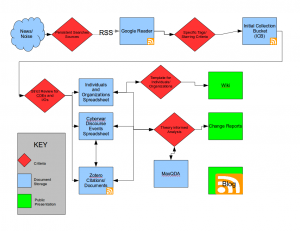

So how can we achieve this? This is where we must drink from the firehose. To do so, we developed a workflow using multiple software packages to track – as far as is possible – the real-time changes to cyber war discourse:

Our method is as follows:

- We first have established persistent Google alerts (such as “cyberwar,” “cybersecurity,” and “hacktivism”) and subscribed to multiple RSS feeds of scholars and experts specializing in cyber security. This is our first mode of extracting useful information from all the online noise.

- This all flows into Google Reader, where we review all of the data in search of what we’re calling Cyberwar Discourse Events (CDEs). CDEs are those government, military, and news documents that are highly cited in the media and which are either reflective of or have the power to shape the overall public discourse about cyber war. Usually they are written by high-ranking politicians, respected think-tanks, and military officials. A recent example is a report from the UN-OECD [PDF].

- Next, we collect the CDEs in a spreadsheet and in the bibliographic program Zotero.

- We then load them into a qualitative analysis program, MaxQDA.

- We review the documents and tag them with a set of codes we have developed for this project. For example, we search for “Threat objects” (that which is being threatened), “Threat subjects” (who is threatening an attack), “Response” (how the military et al would handle an attack), and “Evidence.” These are not all of our tags; there are more, and many more sub-tags.

- In addition, we watch for notable individuals and organizations involved in shaping public discourse about cyberwar. Over the coming months, we will begin “seeding” a wiki with profiles that provide basic information about each of these individuals and organizations, as well as their interconnections.

- Finally, we have a public-facing element, part of which you’re seeing here on this blog. Our intention is to produce periodic “Change Reports” that outline how the debate has shifted over time. We also intend to produce visualized data such as timelines and other charts.

So far, we have gathered and analyzed nearly 80 CDEs, dating back to early 2009. Watch this blog in the coming months for analyses of cyber war discourse. We are already uncovering intriguing patterns and we want to share them with fellow researchers, journalists, policy makers, and civil liberties organizations. And, one major advantage of our method is that much of the data we gather can be followed with RSS feeds. We hope this leads to collaboration with anyone interested in this important debate.

January 25th, 2011 at 4:07 am

[…] of our effort to document and analyze shifts in U.S. cybersecurity discourse, we are coding the Cyberwar Discourse Event (CDE) documents that we collect for the types of evidence that are deployed in support of the claims being made. […]

December 1st, 2011 at 2:42 pm

I have not seen updates in almost a year. Is anyone still working on this?

December 1st, 2011 at 8:24 pm

Jon, the project has slowed considerably since our funding was not renewed. Sean Lawson is still doing work in this area, but the others have moved on to other projects.